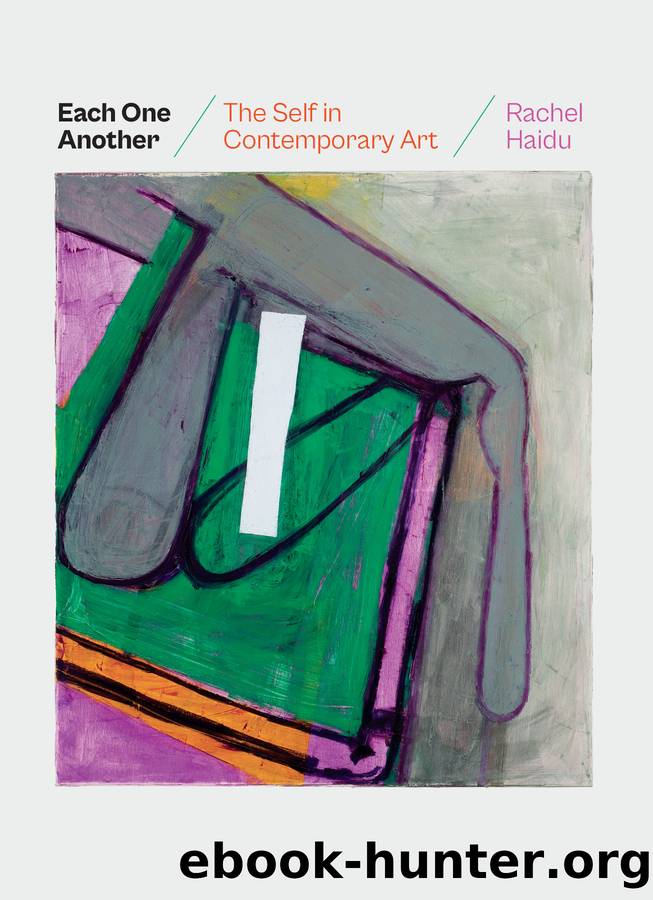

Each One Another by Rachel Haidu

Author:Rachel Haidu [Haidu, Rachel]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: ART000000 ART / General, ART015110 ART / History / Contemporary (1945-)

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2023-08-07T00:00:00+00:00

Sex Panics: Tragedies or Melodramas?

Seeing Brandon as âisolated in soul-sickness against an indifferent city,â James Quandt argues that nothing in this âpassion play to gladden Michelle Bachmannâs heartâ can recoup Shame.16 His review oscillates between defining Shame as a tragedy (a âpassion playâ) and as a melodrama, characterized by its âmoralizing codaâ and âbathetic Barber-like lamentation.â This ambiguity, as it seems to me, rides precisely on those late moments in the film when its narrative is finally trounced by the formal unities I have been describing. For Quandt is particularly irritated by the precise chromatic and sonic interruptions that I have focused on. He notes both chroma and soundâthe sequence in the bathhouse is âluridly lit in Hades red and sordid strobe lightsââand decries McQueenâs deployment of âGlenn Gouldâs lugubrious second recording of the Goldberg Variations over both a showy long tracking shot of Brandon jogging at night and the filmâs histrionic denouement.â Might it then be fair to assume that even if this acute critic is indisposed to submit to the very moments that this drama unfolds its most spectacular effects, they are nonetheless part of what he sees overdetermining Shameâs genre-bending hyperbole? What genres can Shame be seen to bendâand to what effect?

For Blair Hoxby, the defining characteristic of tragedy is its use of pathos. This is true by virtue of âthe end of the genre: to effect through pity and fear the catharsis of such emotionsâ and because of the way tragedy is defined, for Hoxby, by its historical concessions to the spectacular, or what he names as the operatic.17 Those concessions include music and song, costuming and sets. The leveraging of pathos to become the central criterion for tragedy upsets the distinction between theatrical performances and the idealist framework, in which âtheatrical performance is tied to the very appearances that must be dissolved before tragic insight can be generatedâ (emphasis added).18 In other words, Hoxbyâs contention is that tragedyâs spectacle must be so elaborate, in order to âgenerate tragic insight,â that it actually must end in order for that insight to actualize. After all, he reminds us, âthe heroes of tragedy did sing in the Greek theaterâ; thus, âthe representation of pathos might be [the tragedianâs] essential task.â19

What is pathos? It is the genreâs mimetic and performative side, the showing of suffering. âBecause the whole weight of the ancient rhetorical tradition maintained that the best way to move the passions of an audience was to exhibit those passions,â then to think of passion as pathos, as representation, was to reconcile the effects seen onstage with âthe soulâs passive suffering of the strong movements of spirits and fluids in the body when the mind formed some judgment that an object promised good or evil.â20 In other words, pathos is not action but the scene of what it does to a body rendered passive, perhaps even sculptural, plastic. It is only as such effortful, visible accentuation of suffering so acute that it renders the body passive that pathos

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18602)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5450)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3653)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3524)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3505)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3428)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3337)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3287)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3151)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2900)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2897)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2865)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2701)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2701)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2645)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2619)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2564)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2560)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2491)